On the closed window of a café, a small poster reads:

“Via Veneto vestita di luci e colori, ringrazia”

An ink inscription has been added in one of the corners:

“Ringrazia?? Della tristezza totale di una via Veneto che non esiste più???” 1

The advert praises the investment made in holiday decorations. Discreet Christmas lights are wrapped around the trunks of plane trees and magnolias along the avenue. The advertisement itself is quite poor. A colour copy of a blurry picture, three logos, a nostalgic sentence. Four months after the holiday season, the Christmas decorations are still hanging. Roaming its streets today, there is undoubtedly something sinister about this avenue.

Ever since the release of la Dolce Vita,2 the Via Veneto represents, in our collective imagination, the most renowned spot for parties, a place of debauchery for Roman aristocrats and show business celebrities, the flagship of Italian Cinema at the peak of its splendour, an endless gala evening, a ball of luxury cars, a runway of stars, journalists on the lookout, an exalted scenery for a Roma that never sleeps, where musicians and dancers, inexhaustible, give the pace of this frantic choreography. To represent this allegorical fresco of a permanent celebration, Federico Fellini had a replica of a section of the avenue built in the Cinecittà studios, only bigger, brighter, more spectacular. It now seems like the night has fallen on the avenue. Yet, has the Via Veneto ever existed in the way we commonly like to think about it, outside of films and celebrity magazines?

Starting from the Piazza Barberini, the street winds its way uphill until it reaches the Porta Pinciana. On the right side walk, facing north, institutions come one after another: the Chiesa di Santa Maria Immacolata and its crypts decorated with bones, the Palazzo Piacentini of the Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, the Palazzo Margherita of the American Embassy. On the left, the hotel facades: Hotel Alexandra, Hotel Imperiale, Gran Hotel Palace, Hotel Majestic, Baglioni Hotel Regina, Hotel Savoy, Hotel Excelsior; and the bar’s shopfront: Gran Cafe, Cafe de Paris, Harry’s Bar,… All of these use similar arguments, pretending to stand in a dolce vita setting. Many of them are closed, leaving behind them shops now abandoned or under construction. Seizures, economical or health crises have undermined the business of tourist hotels. The various establishments change hands, purchased by pension or sovereign funds, from Singapore, Qatar or anywhere else. The whole neighbourhood is changing. The red disk of the colossal MARTINI sign which overlooked the avenue from the terrace of the building on the corner of Via Bissolati has been removed, like most illuminated signs of the street. It used to escort night owls through the obscurity, simulating a constant electrical twilight.

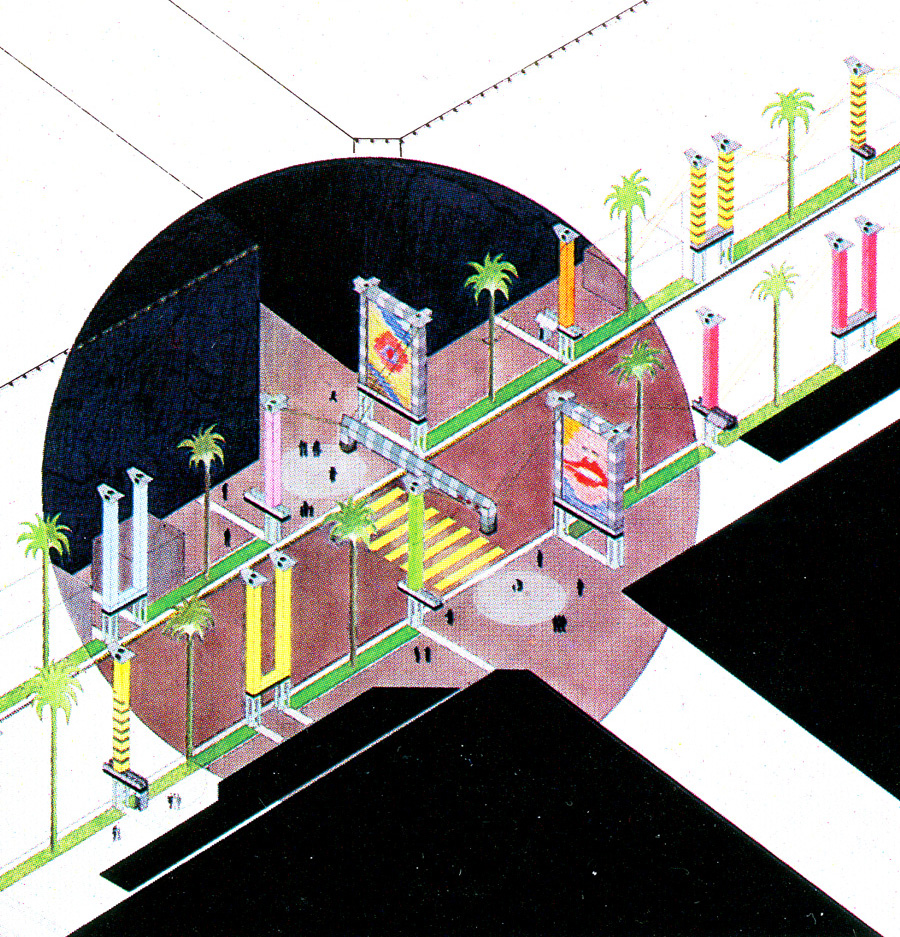

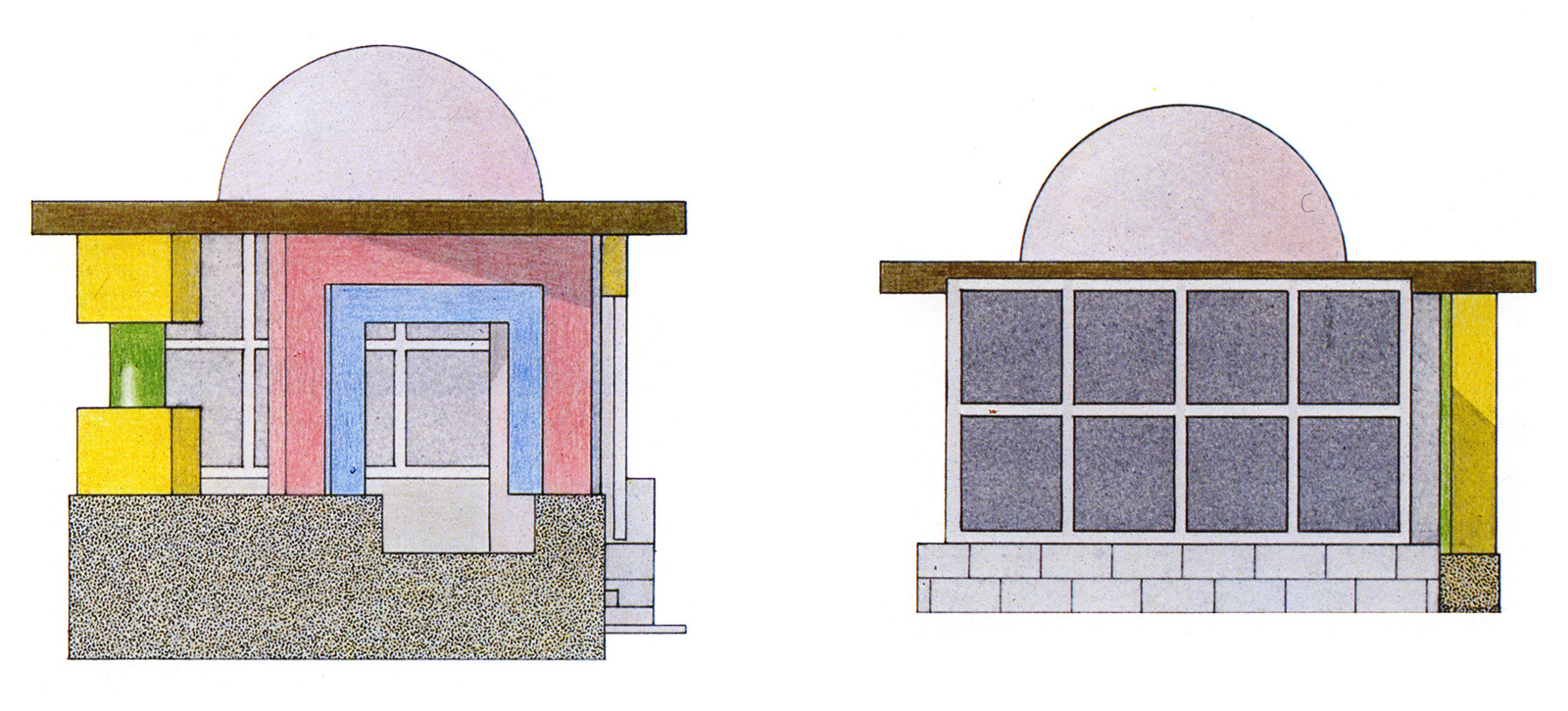

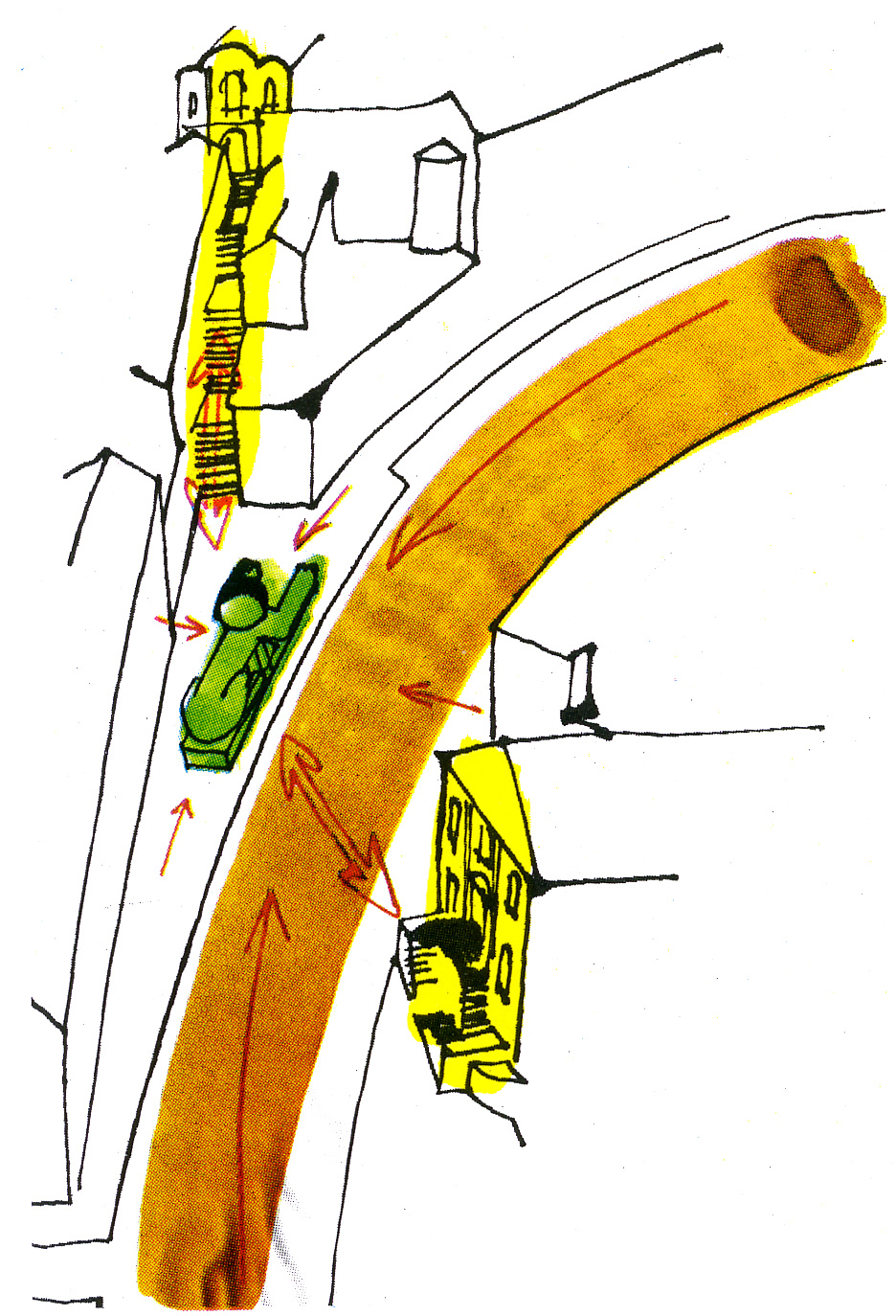

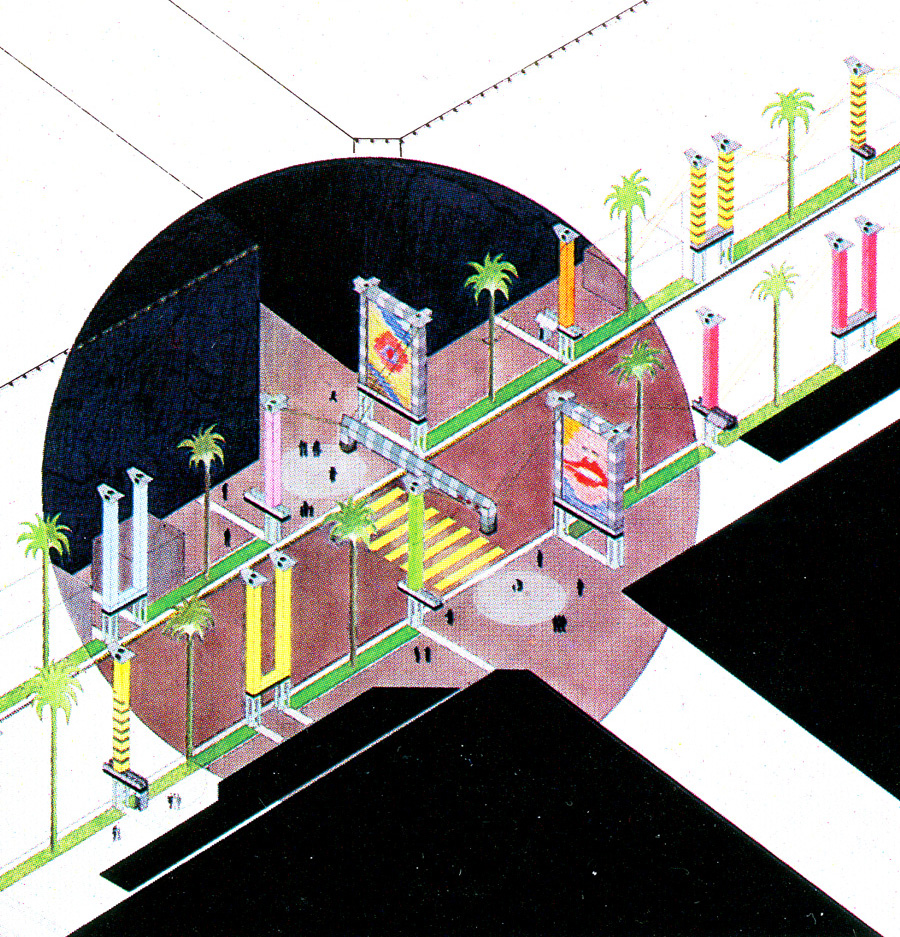

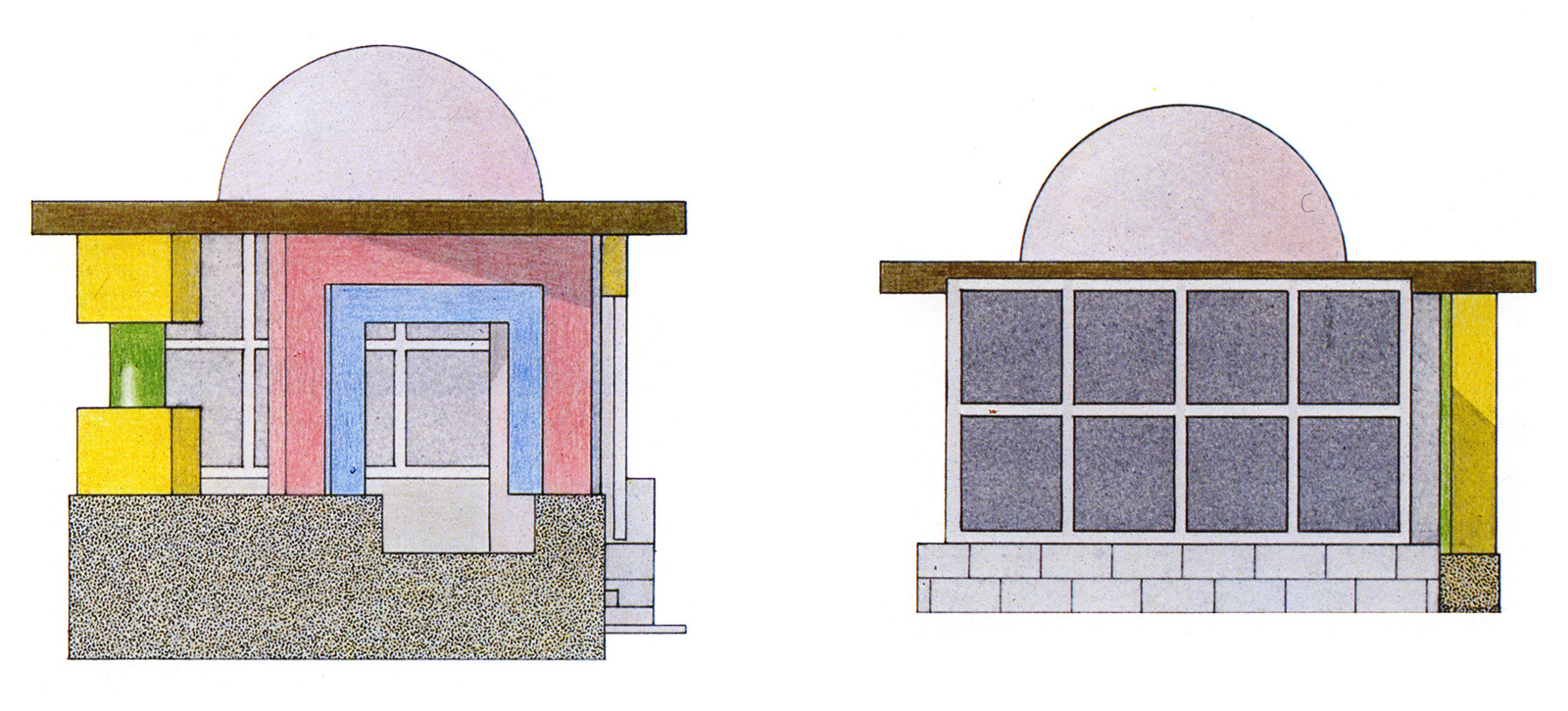

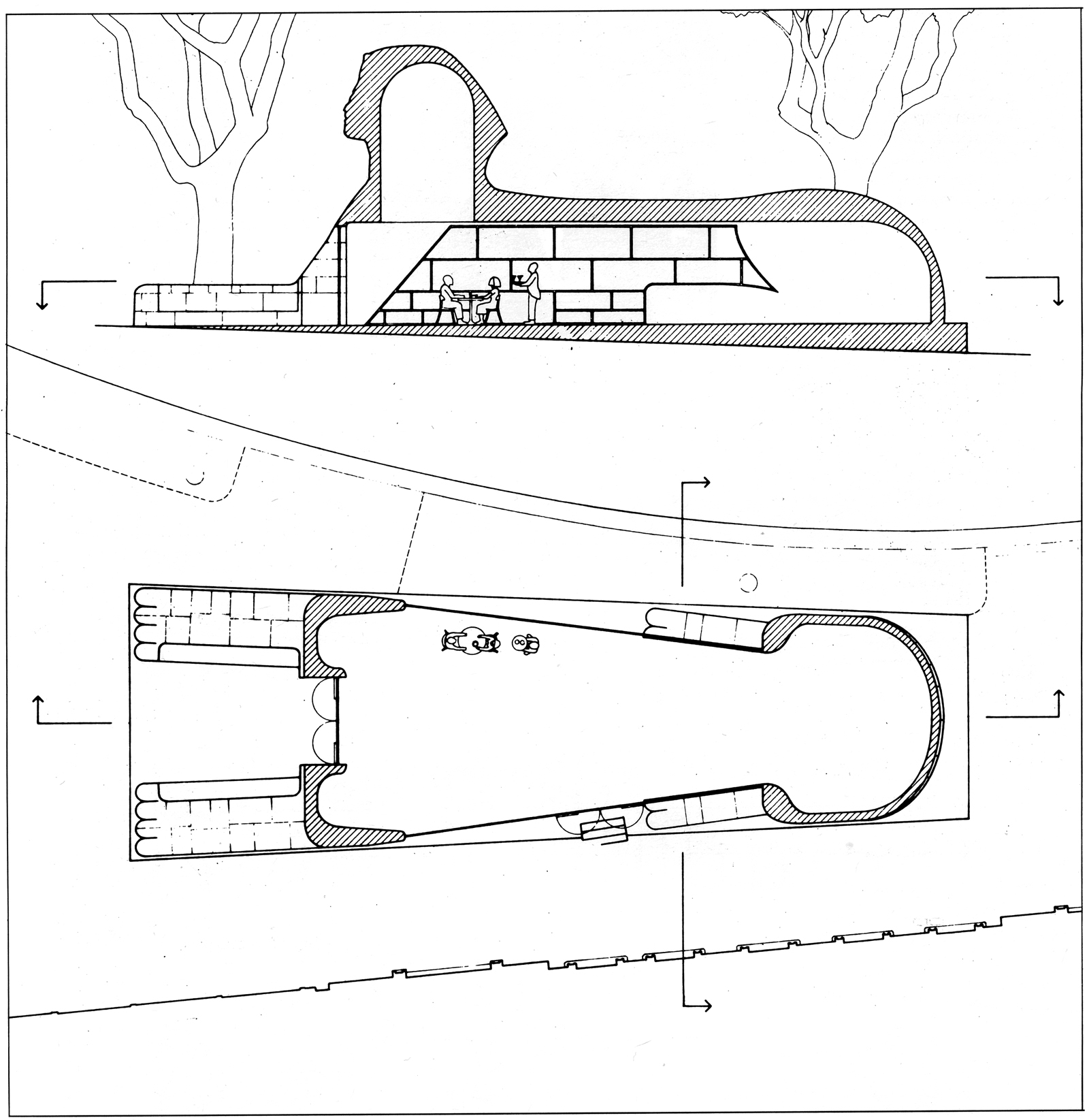

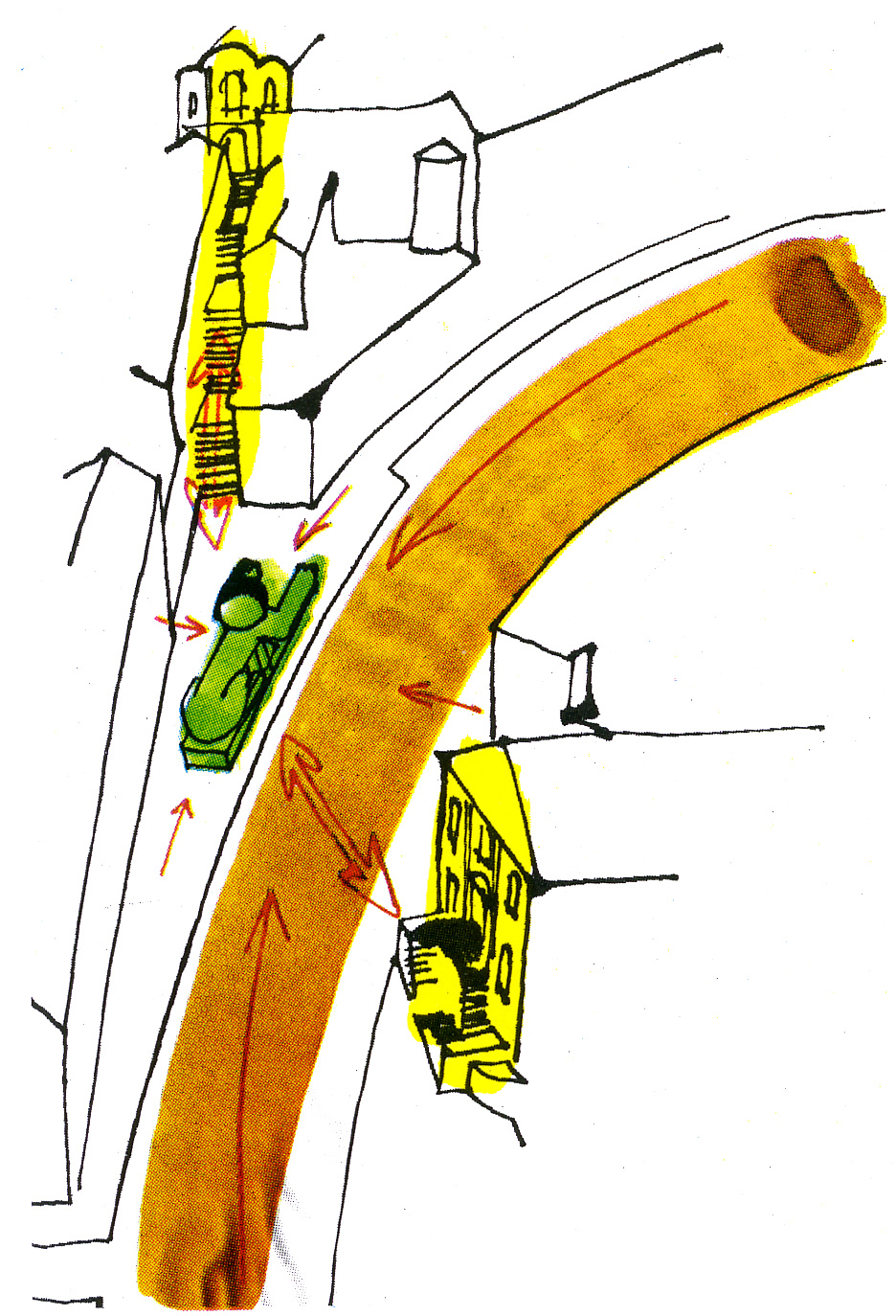

In 1985, twenty teams of Italian architects and designers submitted projects of pavilions connecting the public space to bars, hotels and nightclubs. The sketches of these twenty urbanistic folies are reproduced in a beautiful publication titled Via Veneto, un mito, il suo future, introduced by the urbanist Carlo Aymonino.3 Among these, Alessandro Mendini designed a series of furnished apses for the Café de Paris, Gepi Mariani invented cast iron manhole covers inscribed with the names and addresses of backstreet bars, Massimo Morozzi suggested to mimic the Las Vegas Strip and line up palm trees, billboards and coloured columns on both sides of the pavement,4 Ettore Sottsass submitted the sketch of a raised terrace, covered like a small temple with colourful and chaotic volumes.5 Other projects (a glass tunnel, a truncated Trajan column, a replica facade) turn out to be wiser but guarantee unusual visual and spatial experiences.

By projecting these fairy-tale folies at each and every point of the street, the architecture does not equip the party. It is the party. It embodies the myth of the Dolce Vita which must still be cultivated today. The ghost of the Cinecittà studios on the avenue can only be reinvented through visual overkill, outrageous shapes and unbridled and excessive ideas. Having realised this, Enzo Mari offered to quote a second movie6:

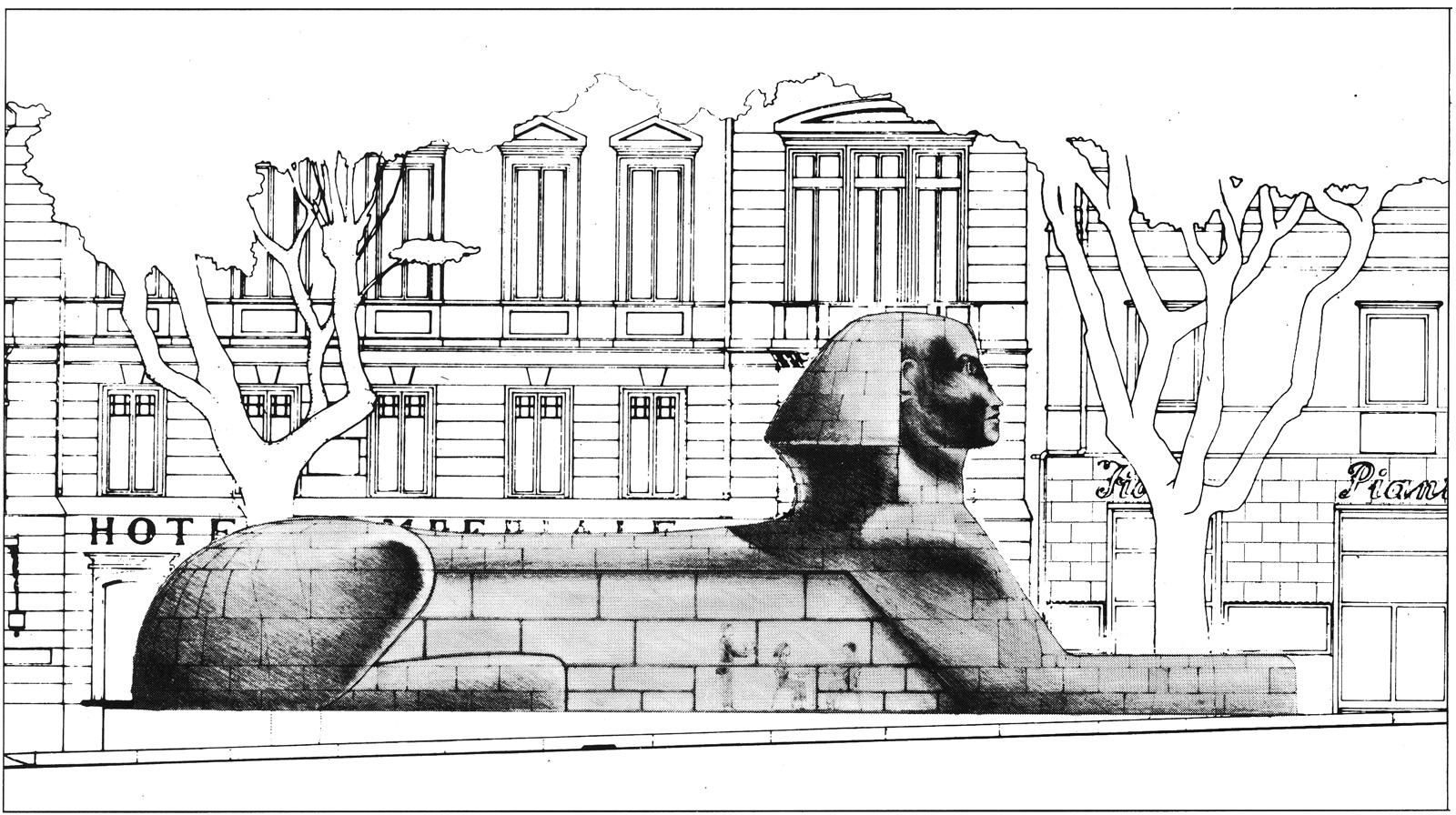

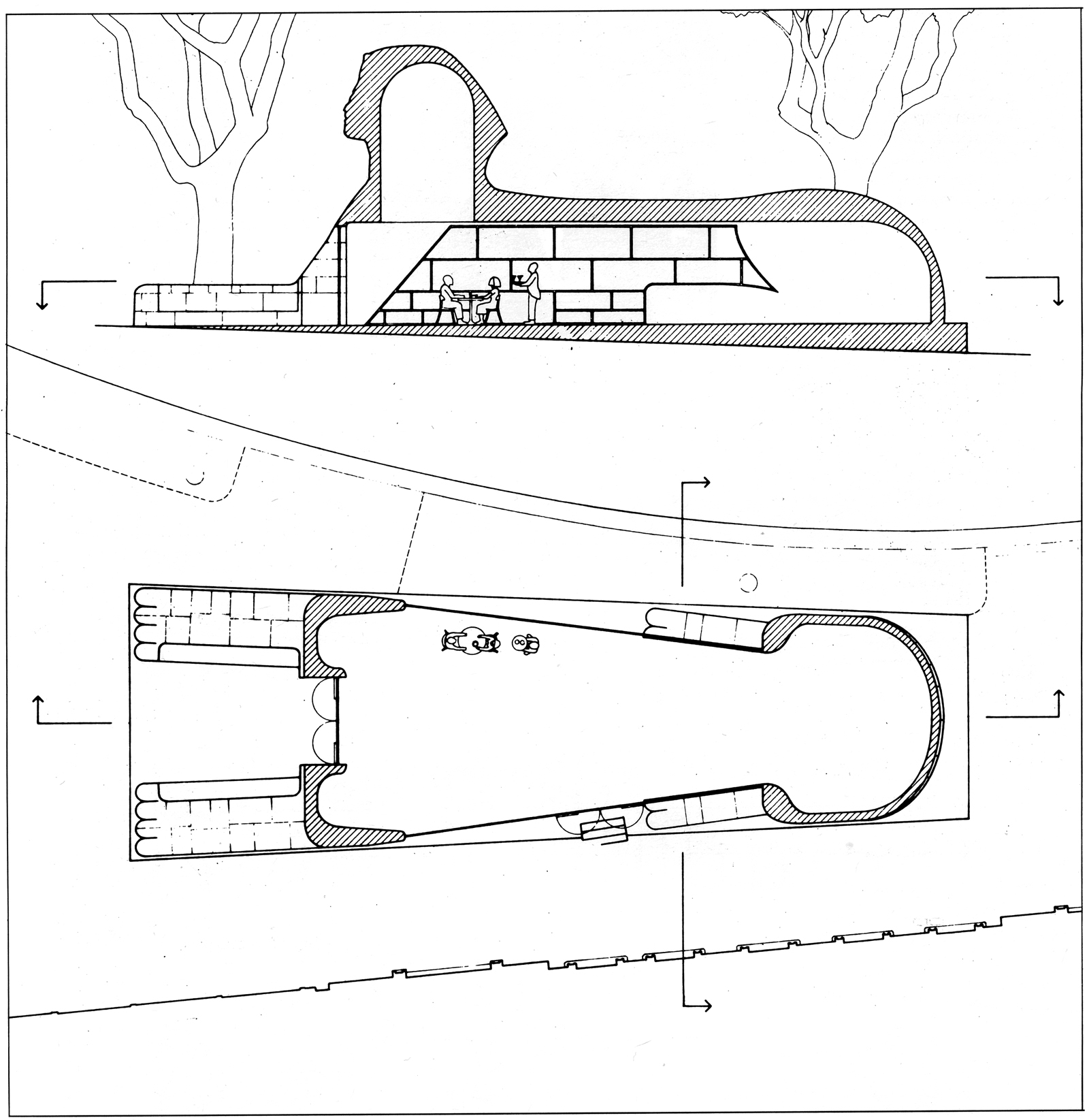

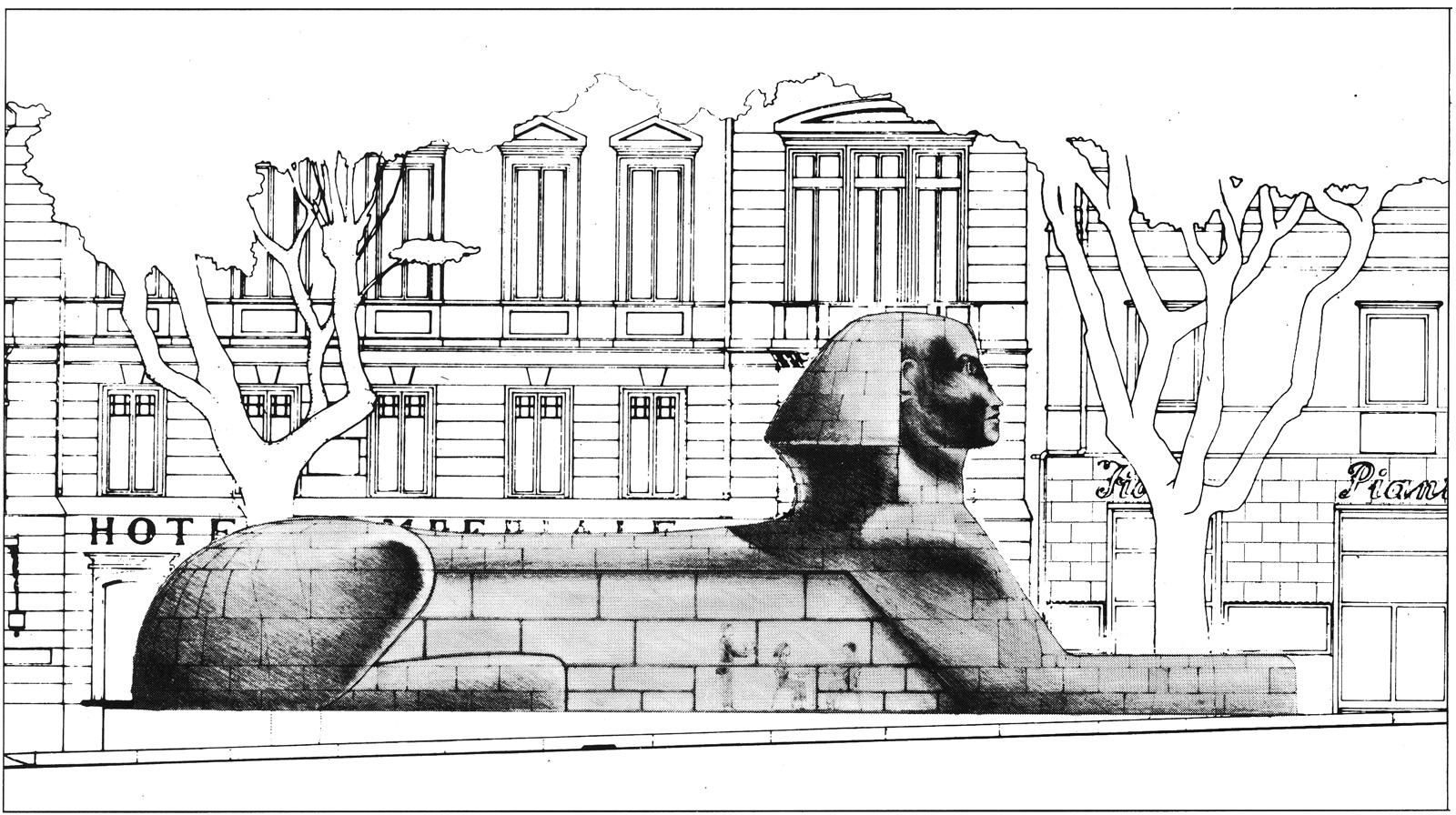

“Da qui la scelta, quale riferimento dell’immaginario collettivo, dell’enorme Sfinge in porfido trainata per le vie di Roma da migliaia di schiavi nel famosissimo film con Elizabeth Taylor”.7

He followed his plan literally and proposed to place a large sphinx in front of the Hotel Imperial, in line with the stairs leading to the Chiesa di Sant’Isidoro. The sphinx covers an area of 90m2 and can accommodate a restaurant for 70 people. The bar’s terrace fits perfectly under the large head. One can sit on its front legs. The Sphinx looks North, so that, as you arrive from Piazza Barberini, the first thing you notice is its ass.

There are no sphinxes on the Via Veneto. The avenue might have been the perfect setting in Rome for the fantasy of architects and designers of the eighties to continue the baroque fantasies of the Fontana del Tritone. Having crossed a Triton kneeling in a giant shell, lifted by dolphin tails spitting water through a conch,8 you might as well be drinking a Spritz between the legs of a big cat with a pharaoh's head. These pavilions haven’t been built, but others can be seen today, clogging up the avenue’s sidewalk. Different from one another, but all painted the same grey. All as boring as each other.

English translation: Melody Robine

On the closed window of a café, a small poster reads:

“Via Veneto vestita di luci e colori, ringrazia”

An ink inscription has been added in one of the corners:

“Ringrazia?? Della tristezza totale di una via Veneto che non esiste più???” 1

The advert praises the investment made in holiday decorations. Discreet Christmas lights are wrapped around the trunks of plane trees and magnolias along the avenue. The advertisement itself is quite poor. A colour copy of a blurry picture, three logos, a nostalgic sentence. Four months after the holiday season, the Christmas decorations are still hanging. Roaming its streets today, there is undoubtedly something sinister about this avenue.

Ever since the release of la Dolce Vita,2 the Via Veneto represents, in our collective imagination, the most renowned spot for parties, a place of debauchery for Roman aristocrats and show business celebrities, the flagship of Italian Cinema at the peak of its splendour, an endless gala evening, a ball of luxury cars, a runway of stars, journalists on the lookout, an exalted scenery for a Roma that never sleeps, where musicians and dancers, inexhaustible, give the pace of this frantic choreography. To represent this allegorical fresco of a permanent celebration, Federico Fellini had a replica of a section of the avenue built in the Cinecittà studios, only bigger, brighter, more spectacular. It now seems like the night has fallen on the avenue. Yet, has the Via Veneto ever existed in the way we commonly like to think about it, outside of films and celebrity magazines?

Starting from the Piazza Barberini, the street winds its way uphill until it reaches the Porta Pinciana. On the right side walk, facing north, institutions come one after another: the Chiesa di Santa Maria Immacolata and its crypts decorated with bones, the Palazzo Piacentini of the Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, the Palazzo Margherita of the American Embassy. On the left, the hotel facades: Hotel Alexandra, Hotel Imperiale, Gran Hotel Palace, Hotel Majestic, Baglioni Hotel Regina, Hotel Savoy, Hotel Excelsior; and the bar’s shopfront: Gran Cafe, Cafe de Paris, Harry’s Bar,… All of these use similar arguments, pretending to stand in a dolce vita setting. Many of them are closed, leaving behind them shops now abandoned or under construction. Seizures, economical or health crises have undermined the business of tourist hotels. The various establishments change hands, purchased by pension or sovereign funds, from Singapore, Qatar or anywhere else. The whole neighbourhood is changing. The red disk of the colossal MARTINI sign which overlooked the avenue from the terrace of the building on the corner of Via Bissolati has been removed, like most illuminated signs of the street. It used to escort night owls through the obscurity, simulating a constant electrical twilight.

In 1985, twenty teams of Italian architects and designers submitted projects of pavilions connecting the public space to bars, hotels and nightclubs. The sketches of these twenty urbanistic folies are reproduced in a beautiful publication titled Via Veneto, un mito, il suo future, introduced by the urbanist Carlo Aymonino.3 Among these, Alessandro Mendini designed a series of furnished apses for the Café de Paris, Gepi Mariani invented cast iron manhole covers inscribed with the names and addresses of backstreet bars, Massimo Morozzi suggested to mimic the Las Vegas Strip and line up palm trees, billboards and coloured columns on both sides of the pavement,4 Ettore Sottsass submitted the sketch of a raised terrace, covered like a small temple with colourful and chaotic volumes.5 Other projects (a glass tunnel, a truncated Trajan column, a replica facade) turn out to be wiser but guarantee unusual visual and spatial experiences.

By projecting these fairy-tale folies at each and every point of the street, the architecture does not equip the party. It is the party. It embodies the myth of the Dolce Vita which must still be cultivated today. The ghost of the Cinecittà studios on the avenue can only be reinvented through visual overkill, outrageous shapes and unbridled and excessive ideas. Having realised this, Enzo Mari offered to quote a second movie6:

“Da qui la scelta, quale riferimento dell’immaginario collettivo, dell’enorme Sfinge in porfido trainata per le vie di Roma da migliaia di schiavi nel famosissimo film con Elizabeth Taylor”.7

He followed his plan literally and proposed to place a large sphinx in front of the Hotel Imperial, in line with the stairs leading to the Chiesa di Sant’Isidoro. The sphinx covers an area of 90m2 and can accommodate a restaurant for 70 people. The bar’s terrace fits perfectly under the large head. One can sit on its front legs. The Sphinx looks North, so that, as you arrive from Piazza Barberini, the first thing you notice is its ass.

There are no sphinxes on the Via Veneto. The avenue might have been the perfect setting in Rome for the fantasy of architects and designers of the eighties to continue the baroque fantasies of the Fontana del Tritone. Having crossed a Triton kneeling in a giant shell, lifted by dolphin tails spitting water through a conch,8 you might as well be drinking a Spritz between the legs of a big cat with a pharaoh's head. These pavilions haven’t been built, but others can be seen today, clogging up the avenue’s sidewalk. Different from one another, but all painted the same grey. All as boring as each other.

- Promotional poster with Acea / Roma Capitale / ‘Via Veneto’ association logos, torn from the window of a closed café, Via Veneto, January 2021. “Via Veneto dressed in lights and colours is grateful. Grateful ?? for the absolute sadness of a Via Veneto that doesn’t exist no more???”

- La Dolce Vita, Federico Fellini, IT 1960, 167’.

- Via Veneto, un mito, il suo futuro, Quarderni di AU, rivista dell’Arredo Urbano, Roma, November 1985.

English translation: Melody Robine